People really hate Thomas Heatherwick’s new Escher-esque “Vessel,” a climbable sculpture in New York City’s billionaire playground of Hudson Yards, and they’re not afraid to wax poetic about it. It’s a stairway to nowhere; a giant shawarma; a pine cone; a beehive; a trash basket; the rib cage of a monstrous robot.

Its name is fitting, some argue, as it’s little more than an empty monument to the outrageous excess with which it’s surrounded. According to Heatherwick, “Vessel” was always meant to be a placeholder name until the public experiences it and helps give it a new one. But with questions of its ultimate accessibility, usefulness and symbolic meaning to the public driving much of this criticism, perhaps the British designer won’t be pleased with the results.

Never thought I would say this but it probably would have been preferable to build an 80,000 seat football stadium that would be empty 80% of the year than the horrendous offering to the mall gods that #HudsonYards appears to behttps://t.co/ybAfk8z8W2

— Jon Auerbach (@JAAuerbach) April 1, 2019

I went to the new 25 Billion dollar #HudsonYards complex, on the very far West Side of Manhatran yesterday. Essentially it is a suburban mall without parking. Very crowded, but seemingly few shoppers. Wonder what will happen when the novelty wears off.

— Frank Didik (@FrankDidik) April 1, 2019

The Hudson Yards sculpture looks like a plus-sized bedbug. #HudsonYards pic.twitter.com/TmSFtLOZBG

— Nick Kolakowski (@nkolakowski) March 30, 2019

More than 1,000 people crowded around the vase of the imposing structure on March 15th, 2019, as it was commemorated and opened to the public. Comprised of 154 interconnecting flights of stairs, including nearly 2,500 individual steps and 80 landings, “Vessel” gives visitors a view of a long-anticipated $25 billion mixed-use complex full of condos that cost between $4 million and $32 million (or more) as well as super-tall office towers, a luxury shopping zone and high-end restaurants. Opening day was chaotic, with crowds pushing up and down every segment of stairway with their selfie sticks waving in the air, leaving few places to rest momentarily before pushing on.

Best take on Vessel at #HudsonYards from Filip Tejchman from @UWM SARUP: “A building that has no function and yet is also somehow LEED certified” ???????? #ACSA107 pic.twitter.com/OGRa6FqWE3

— Dr. Dora Epstein Jones (@DoraEJones) March 30, 2019

Nothing can prepare you for the capitalist altar, that is #HudsonYards #NYC pic.twitter.com/fI2TntAPua

— Richard Jacob (@IdahoNua) April 1, 2019

Urban nightmare. Dystopia. Contemporary panopticon. Yes definitely hate it. #hudsonyards #gentrification https://t.co/UQHHl66pHT

— Professor Laxmi Ram, AICP (@ProfLaxmi) March 30, 2019

Hudson Yard’s billionaire developers, led by Stephen Ross, have framed the Vessel as a benefit to New Yorkers and tourists alike, calling it a public amenity. “We think of this as a three-dimensional public space, like a park, but taller,” says Heatherwick lead designer Stuart Wood. Ross himself notes that Hudson Yards can’t be a playground for billionaires, as it’s been deemed in public discourse, because it has an H&M and a Shake Shack.

It’s fun to hate from afar, but what do visitors have to say about it? Here’s a report from Andrew Russeth of Art News:

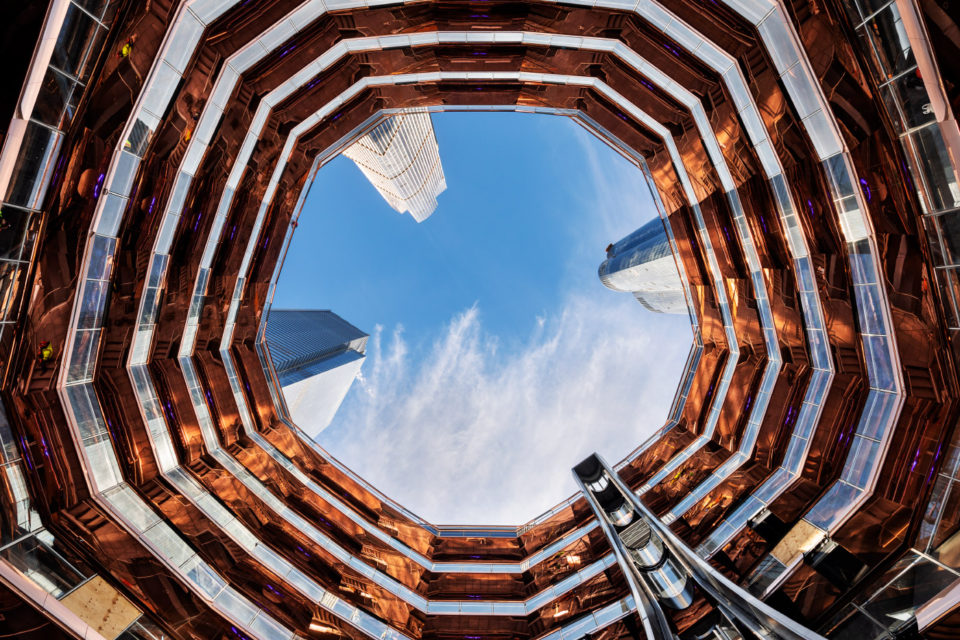

“How is it as an actual aesthetic experience? Very weird, and quite unpleasant, I am happy to report. Looking up from its cramped ground floor, where a panel glows bright blue (a bit like that strange orb President Trump and company touched in Saudi Arabia), you see row after row of the copper-plated steel that lines the staircases, resembling a high-end corporate headquarters or shopping center. It appears to have been specifically designed to induce intense amounts of dread and alienation… for me, it most resembles one of those sets in sci-fi films where members of an alien tribunal gaze down on humans and condemn them to work in salt mines on some distant planet.”

https://twitter.com/carlruiz/status/1109189075846774784

Contest to rename the monstrosity by fake-artist Thomas Hearherwick “The Vessel” in the center of the environmental nullity & rot that is the Dubai on the Hudson #HudsonYards

— Jerry Saltz (@jerrysaltz) March 17, 2019

Rename The Vessel:

1. The Shit-Gibbon

2. Thunderdome.

3. 2060 Underwater Amusement Park.

You??? pic.twitter.com/n6TQojUsLO

I have a feeling we’re not in New York anymore – the grotesque #HudsonYards #longreads https://t.co/vugGsMSDMc

— Anarchie ?? (@junkycosmonaut) March 31, 2019

The story of Hudson Yards is one that has played out on a smaller scale time and time again in New York City and virtually every other city in the world: a story of a piece of land that was devalued by the pollution of industry, marked for redevelopment via lucrative tax breaks and then transformed into something the vast majority of local residents can’t use.

Developers and city officials have long seen the “Far West Side,” which used to be little more than an open pit full of trains, as a blank canvas, with Hudson Yards only emerging as the victor after the death of a dream to host the Olympics in this spot. The platform upon which it’s built is certainly a feat of engineering, and advocates note that the project will add 4,000 new apartments, a school, parkland and as many as 55,000 jobs to the city. The completed portion is only the eastern half; the rest will be under construction through 2024.

In editorial after editorial and thousands of tweets, New Yorkers have expressed their dismay at the fact that this gargantuan project feels so alienating, so wasteful, so clearly not for them. Just as with every condo that goes up in a formerly vacant lot or on the site of a demolished house or business, the investment capital required to complete the project was only ever going to be worth spending if the result was inaccessible to the average person. Gentrification has already wiped out much of the culture that gave New York City its identity, and to many people, Hudson Yards feels like insult after injury. It effectively privatizes the last sizable undeveloped chunk of Manhattan as the gulf between the uber-rich and the rest of us grows ever wider.

At The Guardian, Hamilton Nolan writes, “As urban planning visions go, it is a familiar one: an ultracapitalist equivalent of the Forbidden City, a Chichen Itza with a better mall and slightly better-concealed human sacrifice. The development has been dubbed a ‘billionaire’s fantasy city’, but it is something more sinister than that. It is a billionaire’s reality city. The other 8.6 million of us are just character actors in this drama starring the most unbearable people you can imagine.”

Even The New York Times, the city’s befuddled patrician uncle who’s perpetually behind on trends and utterly tone-deaf, called Hudson Yards “Manhattan’s biggest, newest, slickest gated community,” noting that the project is shifting economic development from other neighborhoods to Hudson Yards without creating new net growth. “It is, at heart, a supersized suburban-style office park, with a shopping mall and a quasi-gated condo community targeted at the 0.1 percent.A relic of dated 2000s thinking, nearly devoid of urban design, it declines to blend into the city grid. From a distance the project may remind you of glass shards on top of a wall.”

It’s not lost on observers that the stairs of the Vessel lead nowhere. The work of climbing is supposed to be the reward, since there’s nothing at the top but a view of the Hudson Yards complex, or, if you turn inward, a view of all the other climbers still making their way up. The structure is just tall enough to pressure people who can climb stairs to do so; its lone elevator only stops at certain platforms, giving people with disabilities a limited experience of a limited experience. It’s only open in hours of daylight, and you have to book (free) tickets 14 days in advance to climb. In doing so, you must agree to a lengthy terms of service agreement stipulating that it’s your own fault if you die or get injured, and that any photos or videos you take and post to social media can be used to promote the attraction.

Removed from this context and all of the cultural baggage it carries, would the Vessel itself produce as much outrage? Perhaps not. Imagine it looming at the edge of a nature preserve instead, as an observation point for a place that can be enjoyed by the whole of a city’s population (with an elevator that goes all the way to the top.)

Curbed’s Alexandra Lange writes, “Rockefeller Center, Battery Park City, the neighborhood that would have been Atlantic Yards—each of these has been and will forever be more boring than the real city. Knowing this, we need to stop letting capital set the urban terms. Cities need to plan their own megaprojects, invest in the transportation network, make those parks, and then let the developers in to fill them out—on the city’s terms. Some of the most transformative urban developments in New York City over the past decade, like Brooklyn Bridge Park, have started with parks.”