Located along a jungle highway in the Amazon around 60 miles from the nearest city, La Pampa was a place you entered at your own risk. At night it was a riot of neon lights and pulsating cumbía music from “prostibar” brothels, frequented by roaming groups of men flush with cash. Neither authorities nor outsiders – and particularly not journalists – were welcome.

This modern-day gold-rush town, home to about 25,000 people, was both a hub for organised crime and people trafficking and a gateway into a treeless, lunar landscape pocked with toxic pools created by illegal gold mining, stretching far into one of the Amazon’s most treasured reserves.

Then, late last month, Peru launched Operation Mercurio 2019, its biggest ever raid on illegal gold mining. By air, land and river, hundreds of army commandos and more than 1,200 police officers swooped on La Pampa.

Peruvians had grown rather used to seeing images of commandos helicoptered into the jungle, driving out miners and blowing up machines in what many suspected was a show for the cameras. But this time, the scale of the operation and the tone of the rhetoric was different.

“We’re not leaving until we see this place green, as it always was,” said Peru’s defence minister, José Huerta. Security forces say they expelled some 6,000 miners, captured dozens of suspected criminals and rescued more than 50 trafficked women in the raid, the result of months of meticulous planning and intelligence gathering.

If the operation continues according to plan, La Pampa – which stretches nearly 20km along the interoceanic highway – will be wiped off the map.

It will not be easy. Although La Pampa started life as a mining camp of wood and plastic sheeting on the side of a highway that connects Peru to Brazil, it is now a fully fledged town. The brick buildings rise up to five storeys high, and it has roomy nightclubs, hotels, corner stores and auto repair workshops. It also has electricity, water, a secondary school and even a church – all built on the illicit economy that developed when international gold prices began their dizzying rise in 2008.

Nevertheless, the security services are determined to destroy it. The town’s infrastructure is being taken apart and businesses are being shut down, be they outright criminal enterprises buying gold or selling contraband diesel or just stores behind on their tax payments. A newly created Amazon Protection Force will man three military bases in the town with 300 soldiers and 150 police officers for an initial six months, according to the government.

A week after the raid, a heavily armed convoy carrying Fabiola Muñoz, the agriculture minister, stopped in La Pampa.

“The principal objective of this operation is that the people understand they can’t be here,” she said.

Behind her, technicians mounted pylons to take down an electrical transformer, leaving a whole block cut off from the grid.

“Entire families are here because they need the work,” Muñoz said. “We can offer them work, decent work – but somewhere else.”

Miners in La Pampa who want to join the formal economy can move to a designated “mining corridor” zone further west, Muñoz said, on three conditions: “No mercury, no child labour and no people trafficking.”

“The people who we find here are not the ones who run the mining activity, who launder money,” she insisted. “The people here are the workers. What we have to do is follow the clues to catch those who are really moving this illegal economy.”

As she spoke, a moody crowd grew.

One woman complained: “For the Venezuelan migrants there’s everything: health, education, all free. But we’re Peruvians and they want to kick us out. It’s not fair.

“We’re not miners. We have a business here. That’s how we make a living. I’ve invested my youth in this business, I live and work here and now they want to put me out on the street.” The woman did not want to give her name.

Peru’s authorities say the evictions must continue.

“This was a no-man’s land,” said Luis Vera, the head of the country’s environmental police force, who had been planning the raid for eight months using undercover agents to identify organised crime ringleaders. Police seized ledgers, payslips and identity documents to be used as evidence in forthcoming prosecutions, and to probe the sources of the big money financing the dirty gold trade.

“There was no authority, there was prostitution, hired killings, [forced] disappearances and people trafficking,” Vera said. “There was every kind of illicit business and all types of crimes with a lot of female victims, including minors. What we’ve done is come in and eradicate the crime.”

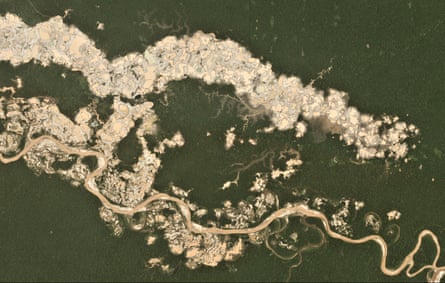

There was also environmental destruction on an epic scale. The south side of La Pampa merges into a 110 sq km scar of clear-cut forest in Tambopata national reserve, one of Peru’s best-known national parks. Illegal mining, which has reached epidemic proportions in six Amazon nations, has left an indelible mark on the ecosystem in this remote jungle region, known as Peru’s “biodiversity capital”.

The raid will finally allow scientists to access the mined areas to see just how bad the devastation is, said Luis Fernandez of the Centre for Amazon Scientific Innovation, who is leading a team assessing how mercury – which is used in the gold extraction process – is affecting human health and the ecosystem.

“It’s an example of the worst you can do to a rainforest,” said Fernandez.

Illegal gold mining has destroyed nearly 960 sq km of rainforest in Madre de Dios since 1985, more than two-thirds of it between 2009 and 2017, according to the centre’s research.

“You cut down all the trees, in the process kill all the animals, destroy the soils … then put a very toxic substance, which is mercury, into the rivers and lakes at the rate of 185 tonnes per year. Recovery of a place with that much damage is going to take a lot longer [than normal],” he said, noting that indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by mercury contamination.

Skyrocketing gold prices have made the illegal trade the most lucrative illicit business in Peru, surpassing cocaine production, according to USAid.

The new governor of Madre de Dios, Luis Hidalgo Okimura, a former medical doctor, backs the crackdown on gold mining, unlike the previous governor.

“Those who want to stay must move somewhere else, or they can go back where they came from,” he said. “But logically we can’t provide work for the 20,000 to 30,000 people who used to live in La Pampa.”

Instead, Peru’s government has pledged 500m soles (£114m) into sustainable development alternatives such as fish farming, agriculture, coffee and cacao. Eco-tourism is already a major draw, with tens of thousands of tourists visiting jungle lodges every year.

Some residents are concerned that when the 60-day state of emergency ends, the miners and criminals will return to La Pampa, or wind up in the regional capital, Puerto Maldonado. Julio Cusurichi, the leader of indigenous federation Fenamad, says the mega-raid could push more miners to invade native territories.

“Those miners will begin to search for other areas, that’s our worry,” said Cusurichi.

Madre de Dios has six protected areas covering more than half its territory and is a haven for indigenous groups in voluntary isolation and initial contact.

“La Pampa was ill-conceived from its beginnings,” Okimura said. “It was a town which the authorities couldn’t even enter. It was a place marked by violence and crime, but today that’s changing.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter