Every day, at 5pm, the gentle melody of the children’s song Yuyake Koyake chimes across the Minato area of Tokyo from a loudspeaker – one of hundreds dotted across schools and parks throughout this megacity of 37 million people.

The daily jingle does more than signify the arrival of evening. It is a test for the system that is designed to save Tokyoites from what would be one of the worst natural disasters in recorded human history: an earthquake striking the centre of the most populous city on Earth.

The last great quake to hit Tokyo was in 1923. Experts estimate the next one is due roughly a century on, with an estimated 70% chance of a magnitude-7 quake hitting Tokyo before 2050. It is no longer a question of if but when the big one will come.

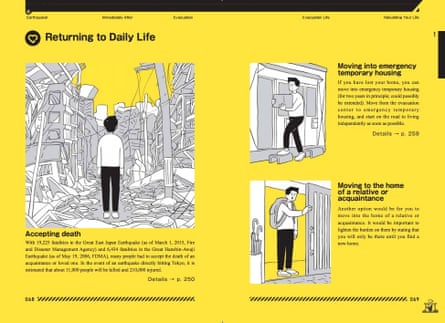

The impact would be devastating. According to an official estimate, a magnitude-7.3 quake striking northern Tokyo Bay could kill 9,700 people and injure almost 150,000. There would be an expected peak of 3.39 million evacuees the day after the disaster, with a further 5.2 million stranded, while more than 300,000 buildings could be destroyed by the earthquake itself or the ensuing fires.

It would be the most calamitous event to confront Tokyo since the US firebombing of March 1945 that killed 100,000 people and burned down more than 267,000 buildings.

Q&AWhat is Guardian Tokyo week?

Show

As Japan's capital enters a year in the spotlight, from the Rugby World up to the 2020 Olympics, Guardian Cities is spending a week reporting live from the largest megacity on Earth. Despite being the world's riskiest place – with 37 million people vulnerable to tsunami, flooding and due a potentially catastrophic earthquake – it is also one of the most resilient, both in its hi-tech design and its pragmatic social structure. Using manga, photography, film and a group of salarimen rappers, we'll hear from the locals how they feel about their famously impenetrable city finally embracing its global crown

When the magnitude-7.9 Great Kanto earthquake struck beneath Oshima Island, about 62 miles (100km) south of central Tokyo, around lunchtime on 1 September 1923, thousands of buildings collapsed. Fires broke out in homes as cooking stoves overturned, and people who escaped described the aftermath as hell on earth. The combined death and injury toll was officially estimated at 105,000 across Tokyo and the adjacent port city of Yokohama, although some reports said it was far higher.

In the chaotic aftermath of the disaster, false rumours about a “Korean revolt” and the alleged poisoning of wells also triggered outbreaks of deadly mob violence against Koreans.

Tokyo has come a long way since 1923. If any city is prepared for an earthquake, it is this one. The hi-tech skyscrapers are designed to sway, the parks feature hidden emergency toilets and benches that turn into cooking stoves, and the city has the world’s largest fire brigade, specifically trained to prevent the kind of flash blazes that spread after earthquakes.

But the problem with earthquakes is that they undermine the very things you do to mitigate them. And with Tokyo now seeing millions of tourists a year, and expecting millions more for the Rugby World Cup this year and the Olympics in 2020, the city is ripe for panic in the event of a disaster.

“Japan is world famous for its resilient infrastructure and for its seismic technologies. If you look around the Tokyo skyscrapers it’s incredible how advanced a lot of technology here is, especially seismic resistance – but my concern is preparedness at the community and individual level,” says Robin Takashi Lewis, a Tokyo-based specialist in disaster preparedness and response.

“In the event of a big earthquake here … there would be significant damage to critical infrastructure such as electricity, gas, water,” Lewis says. After a major quake, the Tokyo metropolitan government says it aims to restore power within a week, water supply in a month and gas within two months. “When you have a city this big and your basic lifelines are out, that’s a very significant problem.”

Yes, Tokyo has the largest urban firefighting force in the world. “But in the case of the ‘big one’, the Tokyo inland earthquake, the emergency services would be overwhelmed.”

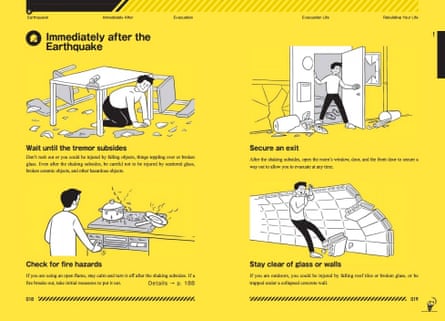

Tokyo householders are urged to secure furniture to the wall using L-shaped brackets, and place wedges under unstable cabinets and anti-slip pads to chair and table legs. Tokyoites are also advised to always store extra canned food and bottled water, as well emergency kits with flashlights, a radio, batteries and everyday medications. Shops sell “emergency toilet bags” that can be attached to a standard household toilet when the water supply is cut off. They are well-drilled to take shelter under tables or to hold cushions or pillows over their heads, to ward off falling objects.

Millions of people, however, could be travelling on Tokyo’s railway and subway network when the quake hits. The Tokyo Metro says its infrastructure has been seismically reinforced, and that trains will make an immediate emergency stop in strong shaking; it advises passengers to hold tightly to handrails and straps.

Preparing for ‘X’ Day

If that all sounds worryingly matter-of-fact, it might be because Japan is uniquely prone to disasters. Earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons ravage it regularly. The most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan, the magnitude-9 disaster off the north-east coast in March 2011, shifted the earth’s axis by up to 25cm and moved the country’s main island, Honshu, 2.4 metres closer to the United States. About 20,000 people lost their lives in the subsequent tsunami, which triggered a meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant.

Naoshi Hirata, a professor of seismology at the University of Tokyo’s Earthquake Research Institute, says the city is at particular risk because two oceanic plates are pushing up against the area – and because Tokyo lies on the flat Kanto Plain, a geological formation that is easily shaken.

The Japanese are used to the concept of natural disasters. Schools and companies commonly hold emergency drills on 1 September, the anniversary of the 1923 quake now known as Disaster Prevention Day. The Tokyo metropolitan government has published a 338-page manual, Let’s Get Prepared, outlining what people should expect from various disasters, and how to reduce their risk.

Distributed to 7 million households and produced in multiple languages, it includes a short manga comic strip called Tokyo ‘X’ Day, starring an office worker navigating scenes of destruction: falling objects, derailed trains, crashed vehicles, damaged buildings and mobile network outages. The story concludes with the words: “This is not a ‘what if’ story. In the near future, this story is sure to become reality.”

The city is also working to update and improve its infrastructure. Although its international image is one of dizzying modern skyscrapers, experts are worried about the city’s traditional fabric: pockets of close-set, wooden houses where fire could spread quickly.

“We still have about 13,000 hectares of concentrated wooden houses, which is about 7% of the area of Tokyo prefecture,” Nobutada Tominaga, an official from the city’s urban development bureau, told an urban resilience forum in Tokyo last month. One recently completed project involved the installation of wide pedestrian zones to help create fire breaks in the older suburb of Nakanobu.

The city also reserves a network of major roads for fire trucks and rescue vehicles. These roads are marked with the sign of a large blue catfish, the Namazu – the giant creature that causes earthquakes in Japanese mythology.

The city has chosen 3,000 schools, community centres and other public facilities to operate as evacuation centres in the event of a major disaster, and there are about 1,200 centres for people who need special care.

Faced with the prospect of 5.2 million stranded people in a major quake, the Tokyo metropolitan government wants to avoid mass movements of workers returning home and advises people to stay where they are at their workplace or school if possible.

Accordingly, business operators are used to keep at least three days’ worth of drinking water, food, and other necessities so that their employees have access to adequate supplies in a disaster. The government has also designated temporary shelters for those people who have nowhere to go, where similar supplies will be available.

Meanwhile, more than 50 sites across Tokyo have been designated as disaster prevention parks. In normal times, they’re used for picnics and other leisure activities, and resemble standard parks in every way except for a grid of manholes in a fenced-off area. After a disaster, the manhole covers are removed and special seats and privacy tents are placed over them, turning them into emergency toilets. The park benches, meanwhile, can be converted into cooking stoves. Emergency response would be coordinated from the Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park, a 13.2 hectare site to the north-west of Tokyo Bay.

Shake-proof buildings

Best known are Tokyo’s shake-proof buildings. The epicentre of the 2011 quake was about 230 miles (370km) away from Tokyo, but the city still felt strong, extended shaking, captured in striking footage that showed skyscrapers swaying like trees in a breeze.

While alarming to those inside, these buildings were doing exactly what they were designed to do: bend and flex instead of snap.

The national building law standards mean there should be “little damage” in a middle-sized earthquake, and that “a building is not to be susceptible to collapse in the event of a major earthquake” of the kind that occurs once in hundreds of years, according to a Tokyo Metropolitan government spokesperson.

Skyscrapers are both the most advanced and get the greatest scrutiny. Buildings over 60 metres must undergo advanced structural analysis as part of more stringent approval processes. Newer skyscrapers in Tokyo feature a range of anti-seismic devices, including large “dampers” to act as a pendulum and counter the earthquake waves, like shock absorbers. The swaying is aided by rubber pads or fluid-filled bases.

The country has also learned from past disasters. In the 1995 Kobe earthquake, most of the collapsed structures had been built before tougher standards were introduced in 1981. Nearly nine in 10 buildings in Tokyo match modern anti-seismic standards, according to a University of Tokyo study.

The city also rolled out projects to reduce risks from other natural hazards, such as floods and storm surges. These include floodgates and levees to protect the eastern lowlands, and improved river and diversion channels in the central area. Where Typhoon Kitty in August 1949 caused a storm surge of 3.15 metres and flooded 137,878 houses, Typhoon Lan, in October 2017, caused a storm surge of 2.98 metres – yet not a single house was flooded.

One of the most remarkable infrastructure projects is known as G-Cans, a 17-year construction project completed in 2009 at a reported cost of 230 billion yen (£1.7bn). G-Cans involves a series of five silos, each 65 metres high, that can collect excess water to prevent flooding. These silos connect to a 6.5km-long tunnel that allows water to flow into a huge underground storage tank. In the particularly rainy August of 2008, when G-Cans was not yet completed, the system still spared damage to local communities by displacing 11.72m cubic metres of flood water.

An Olympic challenge

While the threat of disasters is not a new phenomenon for Japan, the increase in tourism, the steady growth in the number of overseas-born residents, and next year’s Olympic Games pose new challenges because visitors may not be aware of what to do when a quake hits.

Masa Takaya, a spokesperson for Tokyo 2020, says all venues will comply with Japan’s strict building standards, but organisers are also considering “how we ensure that spectators will act in a safe manner if a major earthquake were to occur”.

“To help deal with any emergencies, we are preparing evacuation plans for each venue, and are considering the offer of multilingual support to facilitate prompt and smooth evacuation,” Takaya says.

The city government has deployed multilingual mobile phone apps to help its growing ranks of international residents understand what to do, and Tokyo municipalities have started inviting foreign-born residents to attend hands-on training.

Lewis, the disaster preparedness specialist, says that “given the size and the complexity of this city, the government is doing a good job of preparing its citizens” for a big quake. But there are still “gaps and challenges”.

“There hasn’t been a big earthquake here for several years, and the general level of preparedness at a household level could be higher,” he says.

A lot will come down to the magnitude of the quake and exactly where it strikes. And no matter how prepared Tokyo thinks it might be, it is hard to formally plan for chaos. After the huge earthquake that struck modern, supposedly quake-proof Kobe in 1995, killing 6,434 people and destroying nearly 400,000 buildings – including the elevated Hanshin Expressway, which collapsed – about four in five people requiring rescue were helped by other members of the public rather than the city’s official disaster responders.

When X Day finally arrives, it may be the people of Tokyo themselves who will be called upon to save their own city.

Guardian Cities is live in Tokyo for a special week of in-depth reporting. Share your experiences of the city in the comments below, on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram using #GuardianTokyo, or via email to cities@theguardian.com